Protest signs are hot right now. (Makes sense. There’s a lot to protest.) They’re so hot that some people are even protesting protest signs. Like a lot of you, I was disgusted by that Kendall Jenner Pepsi ad and its images of “diverse” yet uniformly beautiful youths, smiling and waving signs with the vague and aggressively polite “Join the Conversation” slogan. But nothing I’ve read about the debacle quite captured my own feelings on the subject. And other signs have annoyed me too. Seemingly for different reasons.

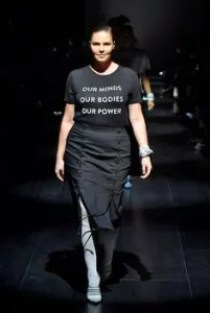

For example, this one:

And these:

In semiotic terms words, of course, are signs. But when those words are put together in the context of a protest sign, the object as a whole also signifies. Traditionally, protest signs have connoted resistance to dominant power structures, challenges to the status quo. They are meant to act as a kind megaphone for voices that go unheard in mainstream media and politics.

For example:

The most obvious source of annoyance regarding the lawn signs, the couture t-shirts and the soda pop ad is that they have transformed objects meant to convey a challenge into commodities for sale. Protest signs are “supposed to be” free; handmade or collectively screenprinted. But I don’t think the problem here is that they’ve lost some mystical anti-capitalist “authenticity,” it’s that they’ve lost their context. In other words, when they became commodities, they became unmoored from the concepts they were meant to signify. They didn’t lose those handmade meanings, instead they began to float.

In the land of semiotics, a floating signifier is one without a stable referent. In other words, rather than refer to a concrete concept in the world (like T-R-E-E stands for a big plant that grows out of the ground), a floating signifier refers to something that has no widely agreed upon meaning. Stuart Hall used the idea to discuss “race,” a concept that exists more through language than biology, and whose meaning shifts depending on power relations, history, national politics, and so on. Roland Barthes thought that images and other non-linguistic signs were more likely to float than words, because images are more open to interpretation. However, they are also more easily naturalized because the distance between sign and referent is collapsed. More simply, if we see a picture, we tend to spend less time consciously translating it in our heads. It seems more “real” and objective than text.

And as the meaning of protest signs float, brands move in to anchor their meanings to a new dock.

If we were to rank the images we’re discussing in order of least to most offensive it would probably go like this:

Lawn signs (Least)

T-shirts

Pepsi ad (Most)

This list also ranks the least to most obviously commodified.

Since myth distorts by presenting ideology as nature, this should be our first clue that it’s probably also ranked from most to least mythological. And this will tell us something about how floating signifiers can help us do more than “join the conversation.”

Let’s try it:

I live in Portland, Oregon. Almost every time I see the lawn sign I re-write it in my head so it says: “In this half million dollar craftsman bungalow occupied by three or four people who are related to each other and, based on the city’s demographics, most likely white…Black Lives Matter,” etc. Or sometimes it’s in a window, so: “In this new construction condo occupied by a single 32-year-old who thinks Portland is hella cheap compared to San Francisco because they don’t have to live on Portland wages…Black Lives Matter,” etc. In other words, while I respect and agree with the sentiment, in the context of Portland – a city experiencing a massive housing crisis that disproportionately impacts the very people listed on the sign – this message seems empty.

Another version is less overtly tied to personal property:

But the fact that it’s sold as a “lawn sign” is still ideological. It presumes one has a lawn. That one has enough control of that patch of land to plant a sign there. The underlying logic of land ownership as power remains (in my case, in a city that is still shaped by and benefitting from its legacy of red-lining).

Prabal Gurung’s t-shirts were “inspired by” slogans on Women’s March protest signs. The media coverage I’ve seen of Gurung’s line has ranged from positive to fawning. And coming from a queer Nepalese-American designer, who made some effort (relative to Fashion Week standards) to exhibit racial and body diversity in his runway show, and to ensure fair wages for the women making the shirts, there does seem to be an earnestness here; an attempt to celebrate rather than appropriate. To use his fashion week exposure as a platform to express his progressive politics.

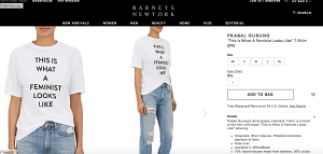

OTOH, this “This is What a Feminist Looks Like” t-shirt sells at Barney’s for $195.00 (a portion of proceeds are donated to Planned Parenthood, the ACLU and others). It is available up to a US size 10 (the average US woman is a size 16). So, while not black and white, I’m getting some clues about what that “feminist looks like.”

OTOH, this “This is What a Feminist Looks Like” t-shirt sells at Barney’s for $195.00 (a portion of proceeds are donated to Planned Parenthood, the ACLU and others). It is available up to a US size 10 (the average US woman is a size 16). So, while not black and white, I’m getting some clues about what that “feminist looks like.”

And then there’s the Pepsi ad. Universally reviled and pulled from the air after one day. Truly a tone deaf, insulting, nauseating, disaster. But are there other reasons why we hated it so much? Could it be that it revealed something we don’t want to see in some of our own protests? A vagueness of messaging? A fraught relationship with the inclusivity we’re espousing? An underlying feeling that a comfortable protest where we don’t really feel any stakes, where a lot of folks seems to be focused on which activist selfie will garner the most instagram followers, isn’t much of a protest? Not saying this is true. Just asking. For a friend.

What I’m trying to say is maybe the problem with the Pepsi ad is that it revealed the floating nature of recent protest slogans, and their susceptibility to being anchored by a brand. This is why I’m suggesting the Pepsi “rally” is the least mythological on our list. Remember, myth functions best when we can’t see it working. Pepsi’s failure was a failure to obscure the machinations of capitalism. It was too desperate in its grasp for the rope that would tie protest meanings to its brand. And since we should be asking those uncomfortable questions anyway, maybe the ad did some good?

What I’m not trying to say is that this floating quality is bad. Floating can be a good thing. There is power in ambiguity. It’s because meaning can never be fixed that we have the power to change how things are. I’m also not saying that events like the Women’s March are meaningless. Quite the opposite.

Arguments I’ve seen about the problem with getting mad at Pepsi are that corporations always do this (a la Give the World a Coke) and that even anti-capitalist protests are actually capitalist. But from what I’ve seen, the post-election marches and slogans and boycotts, are not trying to be anti-capitalist. Maybe they should be, but they aren’t. They are – granted, sometimes vague – demands for equality and recognition. Rights for people of color (race is a floating signifier). Rights for women (gender is a floating signifier). Rights for “science”?? (I mean seriously? That’s where we are?)

Our battle right now is over language and meaning. What does it mean to be a woman? Black? An Immigrant? Poor? Disabled? This isn’t vague or theoretical. When we agree on what a concept means, we also decide how we value it; where we we place it in our larger story. Power and privilege want to keep meanings stable by limiting possible readings. After all, it’s the status quo that gave the privileged their privileges. The cries of fake news show how frightened the powerful are. If everything is open, they tell us, then nothing can be trusted. But we are not saying that anything can mean anything, or fiction is just as true as fact. We are saying that meanings shift. That in order to understand something we have to know its history and context and who benefits from a particular interpretation and who is left out. That is a lot harder, but it’s what we have to do.

Frederick Douglass famously said, “Power concedes nothing without a demand.” Resistance means demanding that we keep signs open even – especially – when we ourselves are uncomfortable with their ambiguity. It means not getting defensive or shutting out the possibility that we might be blind to how the status quo serves us. Sure, this openness makes our messages easy to co-opt. But only if we become complacent and settle for a meaning prescribed by Pepsi or Barney’s or even Etsy. Maybe if we can gain enough momentum in the fight to keep meanings open and inclusive, and keep challenging ourselves to understand how interpretation is never separate from power relations, we’ll be ready to start dismantling capitalism.

In the meantime, if you don’t like your protest being commodified, stop protesting as a consumer. You have other options. Are you a citizen? Claim that, and stand with the undocumented and the stateless. Or get a little old-fashioned and come together as the thing capitalism has made so many of us with less access to capital: workers. And while we’re at it let’s open up the definition of what worker means. There’s room in this boat for everyone, we just need to keep it floating.

Help us make more work like this by heading to our Support Us page! Then follow us on Facebook,Twitter, or Instagram. We’re keeping comments on social media to filter spam. We’d love to hear what you thought and what else you’d like to see.